The Nadir Of Race Relations

| Nadir of American race relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1877 – 1901/1923 (disputed) | |||

Ku Klux Klan on parade in Springfield, Ohio in 1923. | |||

| Including |

| ||

| |||

The nadir of American race relations was the period in African-American history and the history of the Us from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 through the early 20th century when racism in the country, particularly racism against Black Americans, was more open up and pronounced than it had ever been during any other catamenia in the nation's history. During this period, African Americans lost access to many of the civil rights which they had kickoff gained admission to during Reconstruction. Anti-black violence, lynchings, segregation, legalized racial bigotry, and expressions of white supremacy all increased. Asian-Americans were besides not spared from such sentiments.

Historian Rayford Logan coined the phrase in his 1954 book The Negro in American Life and Idea: The Nadir, 1877–1901. Logan tried to decide the year when "the Negro's condition in American society" reached its lowest point. He argued for 1901, suggesting that race relations improved after that twelvemonth; other historians, such as John Hope Franklin and Henry Arthur Callis, argued for dates as late as 1923.[1]

The term continues to exist used; about notably, information technology is used in books by James W. Loewen, and information technology is also used in books past other scholars.[ii] [three] [iv] Loewen chooses afterward dates, arguing that the post-Reconstruction era was in fact i of widespread hope for racial disinterestedness due to idealistic Northern support for civil rights. In Loewen'southward view the true nadir just began when Northern Republicans ceased supporting Southern blacks' rights around 1890, and it lasted until the 2d World State of war. This period followed the financial Panic of 1873 and a standing decline in cotton wool prices. It overlapped with both the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, and was characterized by the nationwide sundown town phenomenon.[5]

Logan'due south focus was exclusively on African Americans in the American South, but the time period which he covered as well represents the worst period of anti-Chinese discrimination and wider anti-Asian discrimination which was due to fear of the so-called Yellowish Peril, which included harassment and violence on the W Coast of the United States, such as the destruction of Chinatown, Denver also as anti-Asian discrimination in Canada,[6] particularly after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Human activity of 1882.[7]

Background [edit]

Reconstruction revisionism [edit]

In the early part of the 20th century, some white historians put forth the merits that Reconstruction was a tragic period, when Republicans who were motivated by revenge and profit used troops to force Southerners to accept corrupt governments that were run by unscrupulous Northerners and unqualified blacks. Such scholars generally dismissed the thought that blacks could always be capable of governing societies.[8]

Notable proponents of this view were referred to as the Dunning School, named after William Archibald Dunning, an influential historian at Columbia Academy. Another Columbia professor, John Burgess, was notorious for writing that "black skin ways membership in a race of men which has never of itself... created any civilization of any kind."[9] [eight]

The Dunning School'due south view of Reconstruction held sway for years. Information technology was represented in D. Westward. Griffith's popular motion-picture show The Nascency of a Nation (1915) and to some extent, it was also represented in Margaret Mitchell'due south novel Gone with the Air current (1934). More than recent historians of the period have rejected many of the Dunning School'south conclusions, and in their place, they offering a different assessment.[10]

History of Reconstruction [edit]

Today's consensus regards Reconstruction every bit a fourth dimension of idealism and promise, a time which was marked by some practical achievements. The Radical Republicans who passed the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were, for the virtually part, motivated by a desire to help freedmen.[10] African-American historian Westward. E. B. Du Bois put this view forward in 1910, and afterward historians Kenneth Stampp and Eric Foner expanded it. The Republican Reconstruction governments had their share of corruption, merely they benefited many whites, and were no more corrupt than Democratic governments or Northern Republican governments.[11]

Furthermore, the Reconstruction governments established public educational activity and social welfare institutions for the get-go time, improving educational activity for both blacks and whites, and they also tried to improve social weather condition for the many people who were left in poverty after the long war. No Reconstruction country authorities was dominated by blacks; in fact, blacks did not achieve a level of representation which was equal to the size of their population in any country.[12]

Origins [edit]

Reconstruction era violence [edit]

"And Not This Man?", Harper'south Weekly, August 5, 1865. Thomas Nast drew this cartoon; in 1865 he, like many Northerners, remembered blacks' military service and favored granting them voting rights.

"Colored Rule in a Reconstructed(?) State", Harper's Weekly, March 14, 1874. Nine years later, Nast'south views on race had inverse. He caricatured blackness legislators as incompetent buffoons.

For several years after the war, the federal government, pushed by Northern opinion, showed that information technology was willing to arbitrate in order to protect the rights of black Americans.[thirteen] There were limits, however, to Republican efforts on behalf of blacks: in Washington, a proposal of country reform fabricated by the Freedmen's Bureau which would have granted blacks plots on the plantation country (forty acres and a mule) they worked never came to laissez passer. In the S, many quondam Confederates were stripped of the right to vote, only they resisted Reconstruction with violence and intimidation. James Loewen notes that between 1865 and 1867, when white Democrats controlled the authorities, whites murdered an boilerplate of one blackness person every 24-hour interval in Hinds Canton, Mississippi. Black schools were peculiarly targeted: school buildings were often burned and teachers were flogged and occasionally murdered.[14] The postwar terrorist group the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) acted with significant local support, attacking freedmen and their white allies; the group was largely suppressed by federal efforts under the Enforcement Acts of 1870–71, merely did non disappear and had a resurgence in the early twentieth century.

Despite these failures, however, blacks continued to vote and nourish schools. Literacy soared, and many African-Americans were elected to local and statewide offices, with several serving in Congress. Because of the black community'south delivery to educational activity, the majority of blacks were literate by 1900.

Continued violence in the South, especially heated around balloter campaigns, sapped Northern intentions. More significantly, after the long years and losses of the Ceremonious War, Northerners had lost heart for the massive commitment of coin and arms that would have been required to stifle the white insurgency. The financial panic of 1873 disrupted the economy nationwide, causing more difficulties. The white insurgency took on new life ten years after the war. Bourgeois white Democrats waged an increasingly violent campaign, with the Colfax and Coushatta massacres in Louisiana in 1873 every bit signs. The next yr saw the formation of paramilitary groups, such as the White League in Louisiana (1874) and Red Shirts in Mississippi and the Carolinas, that worked openly to turn Republicans out of office, disrupt black organizing, and intimidate and suppress black voting. They invited printing coverage.[15] 1 historian described them as "the military arm of the Democratic Party."[sixteen]

In 1874, in a continuation of the disputed gubernatorial ballot of 1872, thousands of White League militiamen fought confronting New Orleans police and Louisiana state militia and won. They turned out the Republican governor and installed the Democrat Samuel D. McEnery, took over the capitol, state firm and armory for a few days, so retreated in the confront of Federal troops. This was known every bit the "Battle of Freedom Place".

End of Reconstruction [edit]

Northerners waffled and finally capitulated to the South, giving up on being able to control election violence. Abolitionist leaders like Horace Greeley began to ally themselves with Democrats in attacking Reconstruction governments. By 1875, there was a Autonomous majority in the House of Representatives. President Ulysses Due south. Grant, who as a general had led the Union to victory in the Ceremonious State of war, initially refused to transport troops to Mississippi in 1875 when the governor of the state asked him to. Violence surrounded the presidential election of 1876 in many areas, beginning a tendency. Subsequently Grant, it would be many years earlier any President would do anything to extend the protection of the law to black people.[17] [18]

Jim Crow laws and terrorism [edit]

White supremacy [edit]

"Believing that the Constitution of the Usa contemplated a authorities to be carried on by an aware people; believing that its framers did not anticipate the enfranchisement of an ignorant population of African origin, and believing that those men of the State of North Carolina, who joined in forming the Wedlock, did not contemplate for their descendants a subjection to an inferior race,

"Nosotros, the undersigned citizens of the city of Wilmington and county of New Hanover, exercise hereby declare that we will no longer exist ruled, and will never again be ruled, by men of African origin.... "

The Wilmington Weekly Star (North Carolina)[19]

November 11, 1898

As noted in a higher place, white paramilitary forces contributed to whites' taking over power in the belatedly 1870s. A cursory coalition of populists took over in some states, but Democrats had returned to power after the 1880s. From 1890 to 1908, they proceeded to pass legislation and constitutional amendments to disenfranchise most blacks and many poor whites, with Mississippi and Louisiana creating new state constitutions in 1890 and 1895 respectively, to disenfranchise African Americans. Democrats used a combination of restrictions on voter registration and voting methods, such every bit poll taxes, literacy and residency requirements, and ballot box changes. The main push came from elite Democrats in the Solid Due south, where blacks were a bulk of voters. The elite Democrats also acted to disenfranchise poor whites.[xx] [21] [22] African Americans were an absolute bulk of the population in Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina, and represented more than 40% of the population in four other former Confederate states. Appropriately, many whites perceived African Americans as a major political threat, because in free and fair elections, they would agree the balance of power in a majority of the S.[23] South Carolina U.South. Senator Ben Tillman proudly proclaimed in 1900, "Nosotros have done our level all-time [to forbid blacks from voting]... we have scratched our heads to find out how we could eliminate the concluding one of them. We stuffed election boxes. Nosotros shot them. Nosotros are not ashamed of it."[24]

Conservative white Democratic governments passed Jim Crow legislation, creating a system of legal racial segregation in public and individual facilities. Blacks were separated in schools and the few hospitals, were restricted in seating on trains, and had to utilize separate sections in some restaurants and public transportation systems. They were often barred from some stores, or forbidden to apply lunchrooms, restrooms and fitting rooms. Considering they could not vote, they could non serve on juries, which meant they had piddling if any legal recourse in the organisation. Between 1889 and 1922, as political disenfranchisement and segregation were beingness established, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) calculates lynchings reached their worst level in history. Well-nigh 3,500 people fell victim to lynching, virtually all of them black men.[25]

Lynchings [edit]

Historian James Loewen notes that lynching emphasized the powerlessness of blacks: "the defining characteristic of a lynching is that the murder takes identify in public, and then everyone knows who did information technology, even so the criminal offence goes unpunished."[26] African American civil rights activist Ida Bell Wells-Barnett conducted one of the get-go systematic studies of the subject. She documented that the most prevalent allegation against lynching victims was murder or attempted murder. She constitute blacks were "lynched for anything or goose egg" – for wife-beating, stealing hogs, existence "saucy to white people", sleeping with a consenting white woman – for being in the incorrect identify at the wrong time.[27]

Blacks who were economically successful faced reprisals or sanctions. When Richard Wright tried to train to become an optometrist and lens-grinder, the other men in the shop threatened him until he was forced to leave. In 1911 blacks were barred from participating in the Kentucky Derby because African Americans won more than than one-half of the first xx-eight races.[28] [29] Through violence and legal restrictions, whites oft prevented blacks from working as common laborers, much less as skilled artisans or in the professions. Nether such atmospheric condition, fifty-fifty the about ambitious and talented black person found it extremely hard to accelerate.

This situation called into question the views of Booker T. Washington, the most prominent black leader during the early on role of the nadir. He had argued that black people could better themselves past hard work and thrift. He believed they had to master basic work before going on to college careers and professional person aspirations. Washington believed his programs trained blacks for the lives they were likely to pb and the jobs they could get in the Southward.

However, as W. E. B. Du Bois stated...

..."it is utterly impossible, under modern competitive methods, for working men and property-owners to defend their rights and exist without the right of suffrage".[30]

Washington had ever (though often clandestinely) supported the right of black suffrage, and had fought confronting disfranchisement laws in Georgia, Louisiana, and other Southern states.[31] This included secretive funding of litigation resulting in Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475 (1903), which lost due to Supreme Court reluctance to interfere with states' rights.

Great migration and national hostility [edit]

African-American migration [edit]

Many blacks left the South in an try to notice amend living and working weather. In 1879, Logan notes, "some 40,000 Negroes virtually stampeded from Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, and Georgia for the Midwest."[ citation needed ] More significantly, offset in about 1915, many blacks moved to Northern cities in what became known every bit the Great Migration. Through the 1930s, more than than 1.v million blacks would leave the South for better lives in the North, seeking work and the chance to escape from lynchings and legal segregation. While they faced difficulties, overall, they had better chances in the North. They had to make great cultural changes, as nearly went from rural areas to major industrial cities, and they also had to adjust from being rural workers to being urban workers. As an example, in its years of expansion, the Pennsylvania Railroad recruited tens of thousands of workers from the Due south. In the South, alarmed whites, worried that their labor force was leaving, often tried to block black migration.[ how? ]

Northern reactions [edit]

During the nadir, Northern areas struggled with upheaval and hostility. In the Midwest and West, many towns posted "sundown" warnings, threatening to kill African Americans who remained overnight. These "Sundown" towns as well expelled African-Americans who had settled in those towns both before and during Reconstruction. Monuments to Confederate State of war expressionless were erected beyond the nation – in Montana, for instance.[32]

Black housing was often segregated in the N. In that location was contest for jobs and housing equally blacks entered cities which were too the destination of millions of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe. As more blacks moved north, they encountered racism where they had to boxing over territory, frequently against indigenous Irish gaelic, who were defending their power base of operations. In some regions, blacks could not serve on juries. Greasepaint shows, in which whites dressed as blacks portrayed African Americans as ignorant clowns, were popular in Northward and Due south. The Supreme Court reflected conservative tendencies and did non overrule Southern constitutional changes resulting in disfranchisement. In 1896, the Court ruled in Plessy 5. Ferguson that "separate just equal" facilities for blacks were constitutional; the Court was made up almost entirely of Northerners.[33] However, equal facilities were rarely provided, as there was no state or federal legislation requiring them. Information technology would non be until 58 years later, with Brown v. Board of Education (1954), that the Court recognized its 1896 error.

While at that place were critics in the scientific customs such as Franz Boas, eugenics and scientific racism were promoted in academia by scientists Lothrop Stoddard and Madison Grant, who argued "scientific bear witness" for the racial superiority of whites and thereby worked to justify racial segregation and 2d-class citizenship for blacks.

Ku Klux Klan [edit]

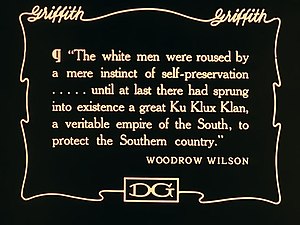

Numerous black people had voted for Democrat Woodrow Wilson in the 1912 election, based on his promise to piece of work for them. Instead, he segregated authorities workplaces and employment in some agencies. The pic The Nativity of a Nation (1915), which celebrated the original Ku Klux Klan, was shown at the White House to President Wilson and his cabinet members. Writing in 1921 to Joseph Tumulty, Wilson said of the pic "I have always felt that this was a very unfortunate production and I wish most sincerely that its production might be avoided, especially in communities where there are so many colored people."[34] [ page needed ]

The Birth of a Nation resulted in the rebirth of the Klan, which in the 1920s had more ability and influence than the original Klan ever did. In 1924, the Klan had 4 million members.[35] Information technology likewise controlled the governorship and a majority of the state legislature in Indiana, and exerted a powerful political influence in Arkansas, Oklahoma, California, Georgia, Oregon, and Texas.[36]

Mob violence and Massacres [edit]

In the years during and afterward Earth State of war I at that place were slap-up social tensions in the nation. In addition to the Great Migration and immigration from Europe, African-American Army veterans, newly demobilized, sought jobs, and as trained soldiers, were less likely to acquiesce to discrimination. Massacres and attacks on blacks that developed out of strikes and economic competition occurred in Houston, Philadelphia, and E St. Louis in 1917.

In 1919 there were violent attacks in several major cities, so many so that the summer of 1919 is known every bit Red Summertime. The Chicago Race anarchism of 1919 erupted into mob violence for several days. It left fifteen whites and 23 blacks expressionless, over 500 injured and more 1,000 homeless.[37] An investigation found that indigenous Irish, who had established their own ability base of operations earlier on the Due south Side, were heavily implicated in the riots. The 1921 Tulsa race massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was fifty-fifty more deadly; white mobs invaded and burned the Greenwood district of Tulsa; one,256 homes were destroyed and 39 people (26 black, 13 white) were confirmed killed, although recent investigations suggest that the number of black deaths could be considerably higher.[38]

Legacy [edit]

Civilization [edit]

Black literacy levels, which rose during Reconstruction, continued to increase through this period. The NAACP was established in 1909, and by 1920 the group won a few important anti-discrimination lawsuits. African Americans, such equally Du Bois and Wells-Barnett, continued the tradition of advocacy, organizing, and journalism which helped spur abolitionism, and also developed new tactics that helped to spur the Civil Rights Motility of the 1950s and 1960s. The Harlem Renaissance and the popularity of jazz music during the early on role of the 20th century made many Americans more aware of black culture and more accepting of black celebrities.

Instability [edit]

Overall, nonetheless, the nadir was a disaster, certainly for black people. Foner points out:

...by the early twentieth century [racism] had become more securely embedded in the nation's culture and politics than at any fourth dimension since the beginning of the antislavery crusade and perhaps in our nation's unabridged history.[39]

Similarly, Loewen argues that the family instability and offense which many sociologists have constitute in blackness communities can be traced, non to slavery, but to the nadir and its backwash.[26]

Foner noted that "none of Reconstruction's blackness officials created a family political dynasty" and concluded that the nadir "aborted the development of the South'due south black political leadership."[forty]

See also [edit]

- Anti-racism

- Ghetto riots (1964–1969)

- Sundown town

- White backlash#The states

- Woodrow Wilson and race

References [edit]

- ^ Logan 1997, p. xxi

- ^ Brown & Webb 2007, pp. 180, 208, 340

- ^ Hornsby 2008, pp. 312, 381, 391

- ^ Martens 207, p. 113 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMartens207 (aid)

- ^ Loewen, James W. (2006). Sundown towns: A subconscious dimension of American racism. New York, NY: Touchstone. ISBN9780743294485. OCLC 71778272.

- ^ Chinese American Club 2010, p. 52 sidebar "The Anti-Chinese Hysteria of 1885–86".

- ^ Weir 2013, p. 130

- ^ a b Katz & Sugrue 1998, p. 92 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKatzSugrue1998 (help)

- ^ William 1905, p. 103 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWilliam1905 (aid)

- ^ a b Current 1987, pp. 446–447 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCurrent1987 (help)

- ^ Foner 2012, p. 388 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFoner2012 (help)

- ^ Current 2012, pp. 446–449 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCurrent2012 (help)

- ^ Current 2012, pp. 449–450 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCurrent2012 (help)

- ^ Loewen 1995, pp. 158–160

- ^ Lemann, Nicholas (2007). Redemption: The Last Boxing of the Civil War. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN978-0-374-24855-0.

- ^ Rable, George C. (1984). Just There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction. Athens, GA: Academy of Georgia Press. ISBN0-8203-0710-6.

- ^ Foner 2002, p. 391

- ^ Electric current 2012, pp. 456–458 harvnb fault: no target: CITEREFCurrent2012 (help)

- ^ "Citizens Aroused / Emphatic Need Made That the Editor of the Infamous Daily Record Get out the Metropolis and Remove His Constitute – An Ultimatum Sent past Committee". The Wilmington Weekly Star. November eleven, 1898. p. ii.

- ^ Kousser, J. Morgan (1974). The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Institution of the One-Party Due south, 1880–1910 . New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN0-300-01696-iv.

- ^ Perman, Michael (2001). Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908. Chapel Hill: University of N Carolina Press. ISBN0-8078-2593-10.

- ^ Current 2012, pp. 457–458 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCurrent2012 (help)

- ^ Chin, Gabriel; Wagner, Randy (April 14, 2011). "The Tyranny of the Minority: Jim Crow and the Counter-Majoritarian Difficulty". Rochester, NY. SSRN 963036.

- ^ Logan 1997, p. 91

- ^ Estes, Steve (2005). I Am a Man!: Race, Manhood, and the Civil Rights Movement. Academy of North Carolina Press. p. Introduction. ISBN9780807829295.

- ^ a b Loewen 1995, p. 166

- ^ Loewen 1995, p. Chapter 5 and 6

- ^ Wright 1945, p. Affiliate 9 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWright1945 (assistance)

- ^ Loewen 1995, pp. 163–164

- ^ (Affiliate 3)

- ^ Robert J. Norrell (2009), Upwards from History: The Life of Booker T. Washington, p. 186-88.

- ^ Loewen 1999, pp. 102–103, 182–183

- ^ Logan 1997, pp. 97–98

- ^ Wilson- A. Scott Berg

- ^ Electric current 2012, p. 693 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCurrent2012 (help)

- ^ Loewen 1999, pp. 161–162

- ^ Current 2012, p. 670 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCurrent2012 (help)

- ^ Loewen 1995, p. 165

- ^ Foner 2002, p. 608

- ^ Foner 2002, p. 604

Sources [edit]

- Brown, David; Webb, Clive (2007). Race in the American South: From Slavery to Civil Rights. Edinburgh, Britain: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN978-0-7486-1376-2.

- Chinese American Order (2010). Sen, Hu; Dong, Jielin (eds.). The rocky road to liberty: a documented history of Chinese immigration and exclusion. Javvin Press. ISBN9781602670280. OCLC 605882577.

- Current, Richard N.; Williams, T. Harry; Friedel, Frank; Brinkley, Alan (1987). American history: a survey (7th ed.). Knopf. ISBN9780394365350. OCLC 14379410.

- Foner, Eric (2002). Reconstruction: America'due south unfinished revolution, 1863-1877. Perennial Classics. ISBN9780060937164. OCLC 48074168.

- Hornsby, Alton Jr., ed. (2008). A Companion to African American History. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 312, 381, 391. ISBN978-i-4051-3735-v . Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- Katz, Michael B.; Sugrue, Thomas J., eds. (1988). "3". Westward.Due east.B. DuBois, race, and the city: "The Philadelphia Negro" and its legacy. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN9780812215939. OCLC 38125924.

- Loewen, James West. (1995). Lies My Instructor Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. New Press. ISBN9781565841000. OCLC 29877812.

- Loewen, James W. (1999). Lies Across America. New York, NY: Touchstone. ISBN0-684-87067-3.

- Loewen, James West. (2006). Sundown towns: A subconscious dimension of American racism. New York, NY: Touchstone. ISBN9780743294485. OCLC 71778272.

- Logan, Rayford Whittingham (1997) [1965]. The betrayal of the Negro, from Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson (Reprint ed.). Da Capo Press. ISBN9780306807589. OCLC 35777358.

- Martens, Allison Marie (2007). A Movement of I's Own? American Social Movements and Constitutional Development in the Twentieth Century. Ann Arbor. ISBN978-0-549-16690-0 . Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- Weir, Robert E. (2013). Workers in America: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN9781598847185. OCLC 827334843.

Additional resources

- Loewen, James W. "Sundown Towns". sundown.tougaloo.edu . Retrieved June 13, 2017.

The Nadir Of Race Relations,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nadir_of_American_race_relations#:~:text=The%20nadir%20of%20American%20race,had%20ever%20been%20during%20any

Posted by: hughesbegadd.blogspot.com

0 Response to "The Nadir Of Race Relations"

Post a Comment